Introduction:

Cerebral venous infarct is an uncommon but important cause of stroke. Clinical and imaging diagnosis is difficult as it does not follow the rules of typical stroke like infarct, intracranial haemorrhage and subarachnoid haemorrhage. Suspicion is the key in diagnosing these cases. Though all ages may be effected by venous infarcts, children and young adults are disproportionately more effected. It effects both sexes, although it is more prevalent in child bearing age (1).

Pathophysiology:

Cerebral venous infarcts are the results of venous occlusion which may be at the level of venous sinuses or the veins. It is different from the arterial infarct due to different anatomical or physiological features of cerebral veins. Elevated cerebral venous & capillary pressure due to venous occlusion can result in a spectrum of phenomena including a dilated venous & capillary bed, development of interstitial edema, increased CSF production, decreased CSF absorption & rupture of venous structures leading to haemorrhage (2). Increased venous & capillary pressure leads to decreased cerebral perfusion causing ischaemic injury manifested by cytotoxic edema. Thrombosis of the venous sinuses also can affect the brain by impairing CSF absorption through the arachnoid granulation resulting in increased intracranial pressure. There is disruption of blood brain barrier leading to vesogenic edema. Increased intracranial pressure in the venous system can lead parenchymal haemorrhage (3).

Causes:

There are plenty of causes which may produce venous infarct. These include pregnancy, post partum period, oral contraceptives, hormone replacement therapy, dehydration, essential thrombocytosis, thrombophilia and other hypercoaguladility syndrome, paraneoplastic syndrome, neoplasm, systemic & local inflammation (d). More than 100 possible factors are identified to predispose CVT, but etiology remains unknown in about 20 – 25% (4).

Clinical Features:

Clinical presentation of CVT is variable and may be acute, subacute or chronic. Commonest symptom of these patients is headache which may be acute or chronic. Acute headache may mimic subarachnoid haemorrhage. There may be features of raised intracranial pressure in the form of papilledema and visual disturbance like diplopia. Focal neurological deficit may be present in some cases, though this is more common in arterial infarct. Focal seizure is again another presentation of CVT.

Venous drainage of brain:

Unlike systemic veins, the cerebral veins and sinuses are valveless and consequently have bidirectional flow (5). Moreover the cerebral venous system does not mirror with cerebral arterial distribution leading to specific pattern of infarct (5, 1). Cerebral venous system is consist of venous sinuses and cerebral veins. The intracranial venous sinuses can be divided into two groups, the superior group containing superior sagittal sinus, inferior sagittal sinus, straight sinus, transverse & sigmoid sinuses. Inferior group comprises of cavernous sinus with interconnecting anterior & posterior intracavernous sinuses, superior & inferior petrosal sinuses which drain to the sigmoid sinuses (6). Cerebral veins are divided into superficial and deep venous system. The superficial venous system comprises of superficial cortical veins and superficial middle cerebral veins with two anastomotic veins, vein of Trolard (superior anastomototic vein) which connect the superficial middle cerebral vein with the superior sagittal sinus and vein of Labbe (inferior anastomototic vein) which connects the superficial middle cerebral vein with the transverse sinus. The deep cortical veins comprises of medullary and subependymal veins that drain into the internal cerebral vein, vein of Galen and straight sinus.

Neuro Imaging:

Plain CT scan of the brain is the first line imaging modality for the cerebral venous thrombosis. It is also preferred for its easy availability, affordability & ease of performing. Two distinct signs may be picked up in plain CT scan of brain – cord sign and delta or dense triangle signs. The cord sign is seen as linear hyperdensity in the vicinity of venous infarcts. Dense triangle sign is seen due to thrombus in the venous sinuses. There are indirect signs which are frequently observed in plain scan, such as infarction, haemorrhagic transformation & intraparenchymal haemorrhage. The cord and dense triangle signs are seen only in 1/3rd of the venous infarcts (7). In CT contrast study, the thrombus is hypodense against the enhancing dural sinuses giving empty delta sign. The contrast CT may be non-contributory in the acute stage when the thrombus appears hyperdense. CT Venogram is very good technique to demonstrate the filling defect in the venous sinuses due to thrombus.

MRI & MR Venogram:

Signal intensity of the thrombus in MRI depends on the time of the event. In the acute phase the thrombus appears isointense to brain on T1 & hypointense on T2 weighed images due to presence of deoxyhaemoglobin in the clot. In subacute stage the clot becomes hyperintense on both T1 & T2 weighted images due to methaemoglobin. In chronic stage the thrombus becomes isointense on T1 & iso or hyperintense on T2 weighted images. The thrombus is hypointense on gradient echo images.

MR Venogram may be performed with or without contrast. Non-contrast MR Venogram may utilize time of flight (TOF) and phase contrast (PC) techniques in both 2D & 3D. In acute thrombus, TOF Venogram shows filling defect against the hyperintense background of slow flow of blood in venous sinuses. However in subacute phase, the thrombus may mimic flowing blood. This can be solved by phase contrast sequence which is not flow dependent. Contrast MR Venogram is more sensitive to diagnose & map out whole thrombus. MR Venogram is performed by injecting contrast in the rate of 1 to 3 cc/s with the acquisition starting at 35 – 45 sec delay. Traditionally 3D contrast enhancing MR (T1 MPRAGE) is better for demonstrating the intracranial venous anatomy (8).

Though DSA is very good technique for assessing the venous thrombus, though it’s use has been drastically reduced due to advent of advanced CT & MRI techniques. In DSA, there is non-visualization of the involved sinus, dilatation of draining veins, prominent collateral veins & retrograde venous flow. In contrast study, the thrombus is hypodense against the enhancing dural sinuses giving empty delta sign. The contrast CT may be non-contributory in the acute stage when the thrombus appears hyperdense. CT Venogram is very good technique to demonstrate the filling defect in the venous sinuses due to thrombus.

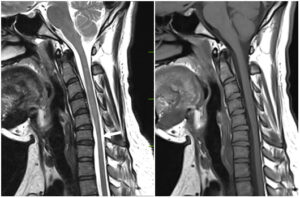

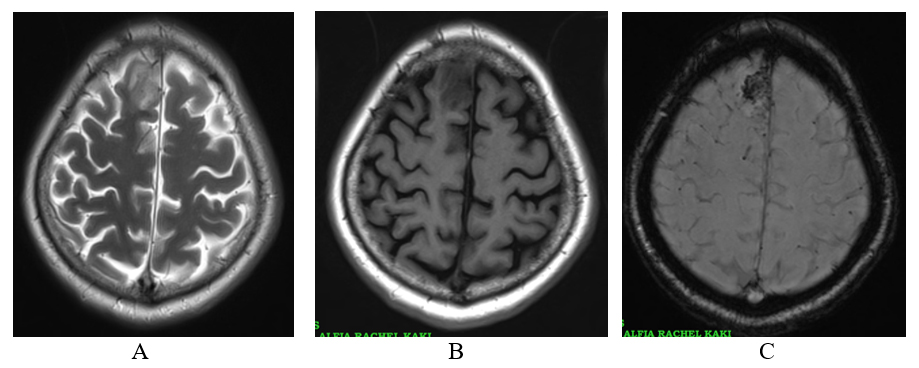

Figure: 1- T2 axial (A) showing hyperintense signal in right superior frontal gyrus which is hypointense on T1 axial (B) & strongly hypointense on GRE (C) images of 53 yrs male patient representing venous infarct.

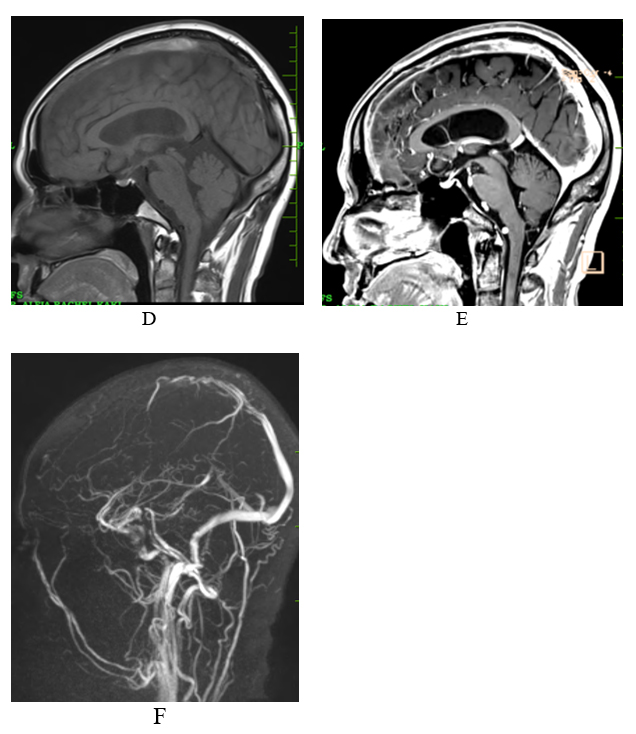

Figure: 1 – T1 sagittal precontrast (D) images show hyperintensity in the superior sagittal sinus, Post contrast 3D MPRAGE (E) show hypointensity in superior sagittal sinus representing thrombus. 3D TOF Venogram (F) shows irregular filling defect in the anterior part of the superior sagittal sinus.

Pitfalls in Imaging:

Increased attenuation in dural sinuses in plain CT may be due to dehydration. To differentiate this physiologic increase in attenuation of the veins from CVT, one has to compare the arteries which also show increased attenuation in dehydration (9). Diagnostic difficulty may occur in the hypoplasia or aplasia of transverse sinuses. The left transverse sinus is frequently seen smaller or absent on non-contrast MR Venogram. In such cases, one has to look for corresponding jugular and sigmoid fossae which are invariably smaller. Contrast Venogram or 3D gradient – recall – echo MRI will easily demonstrate aplasia or hypoplasia from thrombosis. Arachnoid granulation may mimic the filling defect of venous thrombosis. Contrast enhanced MRI or CT can be used to differentiate.

- Sleiman K, Zimny A, Kowalczyk E, Sasiadek M. Acute cerebrovascular incident in a young woman: venous or arterial stroke? – Comparative analysis based on two case reports. Polish J Radiol. (2013) 78:70–8. doi: 10.12659/PJR.889616

- Schaller, R. Grant. Cerebral venous infarction: The pathological concept. Cardio-vascular disease. 2004; 18 (3): 179 – 88

- Tadi P, Behgam B, Baruffi S. Cerebral venous thrombosis. In: StatPerls (internal). Treasure Island (FL): StatPerls publishing: 2023 Jan.

- Walecki J. Postępy Neuroradiologii. Vol. 21. Polska Fundacja Upowszechniania Nauki; Warszawa: 2007. pp. 495–98. [in Polish] [Google Scholar]

- Osborn AG. Venous anatomy and occlusions. In: Osborn AG, editor. Osborn’s Brain. Salt Lake City: Elsevier (2017). p. 254–76.

- Rhoton AL jr, The cerebral veins. Neuro-surgery 51 (4 suppliment): S159-0205

- Ulivi L, Squitieri M, Cohen H, Cowley P, Werring DJ. Cerebral venous thrombosis: a practical guide. Pract Neurol. 2020 Oct;20(5):356-367. [PubMed]

- Leach J.L., Fortuna R.B., Jones B.V., Gaskill-Shipley M.F. Imaging of cerebral venous thrombosis: Current techniques, spectrum of findings, and diagnostic pitfalls. RadioGraphics. 2006;26:S19–S41. doi: 10.1148/rg.26si055174. – DOI – PubMed

- Provenxak JM, Kranz PG, Dural sinus thrombosis: sources of error in image interpretation. AJR 2011; 196 (I): 23 – 31.